Reviews

Several Gravities

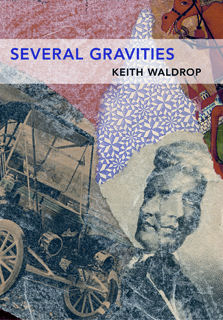

by Keith Waldrop

Several Gravities

by Keith Waldrop

Edited and with an introduction by Robert Seydel

Color & b/w illustrations

Siglio Press, 2009; 112 pages; $39.50

ISBN: 978-0-9799562-1-8, casebound

http://www.sigliopress.com

Reviewed by Sarah White

Keith Waldrop's career as a poet, publisher, translator, essayist and memoirist has never trapped him in a labyrinth of words. Or, if it has, he has regularly escaped from it into a forest of images. There he has fashioned hundreds of complex collages some thirty of which are reproduced in Several Gravities alongside the artist's statements on process, a selection of his poems, and an extensive editorial essay by his editor, Robert Seydel.

Waldrop is far from unique as a writer active in the visual arts. A recent compendium, The Writer's Brush (Mid-List Press, 2007), compiles over 200 such writers and only begins to cover the territory. Many adults and most children are happiest when they are making something. Yet few of us can spend all day seven days a week making poems. Waldrop, interviewed by poet Peter Gizzi, speaks of a continuous "desire of the thing to be created" which in turn furnishes energy for creation.

Several Gravities offers makers and readers of poetry a lot to think about. It raises aesthetic questions applicable to either verbal or visual artifacts. For example, Waldrop speaks of drawing on collage techniques in one (though by no means all) of his poems, "Falling in Love Through a Description" (in Transcendental Studies: A Trilogy, Berkeley, 2009). He has appropriated (he says "stolen") words and phrases from non-poetry books, fashioning disparate elements into stanzas and rearranging them alphabetically, guided, he declares, not by strict aleatory practice à la John Cage but by his own inclinations ("mon plaisir"). Such procedures, as Waldrop observes, "encourage abstraction." They also risk eliciting in reader or viewer a sense that the elements selected and combined are maddeningly arbitrary, that anything goes, and that anybody (e.g. "my five-year-old child") could do it. What, asks the reader or viewer, makes this a whole poem or picture? Waldrop pursues the issue without aspiring to settle it:

What might ordinarily hold a work together—character, for instance, or chronology—often loses out to foreign bodies appearing from other environments. Stability is then a matter of what … I call[ed] 'formal grip.'" In his poem "The Luxury of Hesitation," we find ellipses and unexplained spaces throughout until the concluding lines, a quite explicit personal statement:

I would like to be

beautiful when

written.

Elsewhere, he says of his pictures "collage is for me a way to explore, not necessarily the thing I am tearing up, but the thing I am contriving to build out of torn pieces. To the extent that there is a purpose to what I do, its end is 'the enjoyment of composition,' a concern, as Whitehead notes, common to aesthetics and logic."

Based on the artist's remarks we are not surprised to find the collages themselves enigmatic (not subject to literal explication) yet conscientiously unified. In one untitled work (9" x 16", here reduced to 5" x 9") the heads of two stone angels (or the same angel oriented in two directions) emerge from a shadowy slate blue background and dominate the left side of the picture. To the right of one angel's face, a gloved, booted, helmeted black and orange comic book superhero stands in attack mode. This figure wears a medallion inscribed with the number 13 and, in his threatening pose, might easily outbalance the gray angels but does not because it is so small by comparison, as is the unidentifiable building—hotel? cabana?— behind him which, once again, would throw the picture askew were it not so much smaller in scale than the two heads, and if it did not recede into the dark blue background thanks to a careful layering of materials. There is bliss in the expression of one stone angel and eroticism in the gesture of the other, who appears to be planting a kiss on the face of his twin. The major elements—angels, comic book hero and building—are heterogeneous, unreadable as puzzle or rebus. Nor do they seem to suggest a single salient joke of the kind seen in John Ashbery's collages. Yet the figures are held together by skillful incorporation into the same shadowy blue world. Regrettably, this collage, reproduced on one spread (two facing pages), suffers from the heavy gutter straight down its center. Moreover, none of the plates in Several Gravities allow us to appreciate subtle layerings or varied textures. Imagery is clear and colors articulate, but much has surely been lost in translating the originals into a format suitable for binding into a 6" x 9 ½" book.

Yet the volume is a pleasure to hold, more compact than the usual art monograph, sturdier than a paperback, and unusually rich with images and ideas related to creative life.

Sarah White lives in Manhattan, where she writes, paints and does collages. She is author of one poetry collection, Cleopatra Haunts the Hudson (Spuyten Duyvil, 2007), a chapbook, "Mrs. Bliss and the Paper Spouses," (Pudding House, 2007) and has a book-length lyric essay, The Poem Has Reasons: a Story of Far Love on line at www.proempress.com.