Articles

Eugene Ionesco (1909-1988): The Avant-God of Absurdistan

Eugene Ionesco's Centennial 1909-2009

by Valery Oisteanu

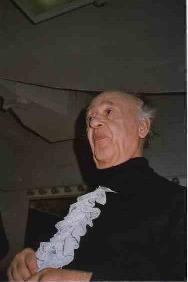

Eugene Ionesco

Photo by Valery Oisteanu

Motto: "Pray to the I don't-know-who: Jesus Christ, I hope"

(Inscription on Ionesco's grave in Montparnasse cemetery, Paris)

The Theatre of the Absurd is a didactic designation for plays written by European drama writers in the late 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, as well as a name for a style of theatre, that has evolved from such works. The term was coined by the critic Martin Esslin (Jewish-Hungarian/English), who made it the title of his book published in 1961.

"The theatre of the absurd strives to express its sense of the senselessness of the human condition and the inadequacy of the rational approach by the open abandonment of rational devices and discursive thought."

Esslin compared Absurd Drama to "The Myth of Sisyphus" by Albert Camus; whose existentialist philosophy asserted that life is inherently without meaning. This term is applied to a wide range of plays, with horrific or tragic images, including characters caught in hopeless situations forced to repeat meaningless actions, dialogue full of funny clichés, and nonsensical wordplay, as well as plots that are cyclical or absurdly expansive. In the first (1961) edition, Esslin presented the four defining playwrights of the movement as Samuel Beckett, Arthur Adamov, Eugene Ionesco, and Jean Genet, and in subsequent editions he added a fifth playwright, Harold Pinter — although each of these writers has unique preoccupations and techniques that go beyond the term "absurd." Other writers whom Esslin associated with this group include Tom Stoppard, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Fernando Arrabal, and Edward Albee.

How did Eugene come to such an existential-surreal-absurd revelation? According to some literary historians such as Deborah B. Gaensbauer who writes in "Eugene Ionesco Revisited": "Walking in summer sunshine in a white-washed provincial village under an intense blue sky, Ionesco was profoundly altered by the light." She introduces as a starting point a spiritual transcendence. He was struck very suddenly with a feeling of intense luminosity, the feeling of floating off the ground and an overwhelming feeling of well-being. When he "floated" back to the ground and the "light" left him, he saw that the real world in comparison was full of decay, corruption and meaningless repetitive action. This also coincided with the revelation that death takes everyone in the end.

My approach to Ionesco's work is a bit more poetic; "a dada/surrealist current in drama" evolved as follows: first was Alfred Jarry's Ubu followed by his compatriots' Urmuz and Tristan, Tzara's Cabaret Voltaire, then Antonin Artaud's Theater of Cruelty, that evolve into Cocteau's films, Jean Genet's theater and Roger Vitrac's plays later to blossom as Ionesco's and Beckett's absurd dramas.

It is sad that Ionesco never acknowledged or promoted the Romanian-French Avant-garde and Surrealist influence, or that of French culture, and the people that lived and created side by side with him in Bucharest and Paris: Tzara, Brancusi, Brauner, Herold, Luca, Fundoianu, Voronca, Isou, Perahim, Paun and Trost.

Pessimistic existentialist with surrealist dreams, Ionesco demonstrates a disgust for the world, a distrust of communication, and the subtle sense that a better world lies just beyond our reach. Echoes of this pessimism can be seen in his important works: characters pining for an unattainable "city of lights" (The Killer, The Chairs) or perceiving a world beyond (A Stroll in the Air); characters granted the ability to fly (A Stroll in the Air, Amédée); the banality of the world which often leads to depression (the Bérenger character); ecstatic revelations of beauty within a pessimistic framework (Amédée, The Chairs, the Bérenger character); and the comic-sarcastic inevitability of death (Exit the King).

While still a student, Donald Watson, who translated most of Ionesco's plays into English from French, met Ionesco by chance and heard him complaining that there were no English translations. Ionesco said, "Why don't you do it" and the rest is history. Watson translated many of the author's books, his journal, and most of the plays, all published by Barney Rossett in Evergreen books in the 1960s.

Exit The King is a pure slapstick Broadway production not really worthy of Ionesco. Geofrey Rush's vulgarization of speech and pedestrian vision transform Ionesco's play into a fun comedy with loud sound effects, including earthquakes and vaudeville atmosphere. Susan Sarandon and the guard character are the only actors on stage who seem to understand the tone of Absurdity.

"I thought that it was strange to assume that it was abnormal for anyone to be forever asking questions about the nature of the universe, about what the human condition really was, my condition, what I was doing here, if there was really something to do. It seemed to me on the contrary that it was abnormal for people not to think about it, for them to allow themselves to live, as it were, unconsciously. Perhaps it's because everyone, all the others, are convinced in some unformulated, irrational way that one day everything will be made clear. Perhaps there will be a morning of grace for humanity. Perhaps there will be a morning of grace for me." (Richard Seaver's translation of "The Hermit," Mercure de France, 1973, Seavers books.)

"Eugene Ionesco News," a new section on The New York Times website, archives articles about Eugene Ionesco.

Right smack on the first page (updated info March 28, 2009) Mel Gussow states:

"He was born in Slatina, Romania, on Nov. 26, 1909, although he took three years off his age and claimed 1912 as his birth year, presumably because he wanted to have made his name before the age of 40. His father was Romanian, his mother French. In 1939, he moved back to France and worked for a publisher. He became a French citizen and remained there for the rest of his life. During World War II, he and his wife were in hiding in the south of France." Well, Mr. Gussow, not exactly, get your info correctly. Ionesco was a survivor but not a hero.

There are many versions of those years, in the published books in France and Romania, but not one comes close to such laughable distortion of the historical events.

When World War II was declared Ionesco went back to Romania from France. He worked as a French teacher at Sfântul Sava in Bucharest. The situation in Romania was so bad that he bitterly regretted having left Paris and, after many failed attempts, finally returned to France in May 1942 with his wife, thanks to friends who helped them to get travel documents for an official mission. As he put it," I am like an escaped prisoner who flees in the uniform of a jailer."

At first Eugene and Rodica lived in Hôtel de la Poste in Marseilles. They had great financial difficulties. He translated and prefaced the novel "Urcan Batrânul" (Father Urcan) by Pavel Dan (1907-1937). Eugene Ionesco was appointed to the cultural services of the Royal Legation of Romania in Vichy, becoming cultural attaché. His daughter Marie-France was born on August 26, 1944.

Another version of the same events is as follows: Eugene Ionesco was sent by the Antonescu government (a repressive militaristic regime, part of the German axis) as a press attaché to the Romanian Embassy in the Vichy government, with his wife Rodica in May, 1942. He worked diligently as a functionary and advanced to cultural secretary II until 1 October 1945. Alexandra Laignel-Lavastine and Marie-France Ionesco —each with a book published and translated in several languages—contain contradictory accounts of those years. (Marie-France Ionesco: Portrait of a Writer in his Century 1909-1994 (Romanian translation) Bucharest, Humanitas-2004.)

The controversy involves Ionesco's relation to Nazi-sympathizers and his Jewish friends from Romania and France. Some sources maintain that although he lived close to Cioran he avoided his company, but the reality was that Eliade and Cioran were his close friends since their student days at the University of Bucharest and also the two (Cioran & Eliade) were early Romanian-Fascist sympathizers, but subsequently, supposedly changed their minds.

What upset me reading "Portrait of a Writer in his Century: Eugene Ionesco 1909-1994," the book by Marie-France Ionesco, is that by defending her father, she defends a brutal fascist tyrant. On pg. 115 she says that "Gen. Antonescu was tried and convicted under the charge of war crimes, paying with his life," hinting that he was not directly responsible, because the situation was impossible to avoid. In the next paragraph she reports that Ionesco regretted the conversation he had with Antonescu, in which he gave veiled indications of the approach of allied forces as early as 1942. But this is her version and I will consider it as a secondary source or hearsay because she was not even born at that time.

In Alexandra Laignel-Lavastine's "Cioran, Eliade, Ionesco L'ubli de fascism" (PUF, Paris, 2002), on pg. 358-359, she reveals the supposed refusal of a (un-named) "cultural secretary" from the Romanian Embassy to cooperate in the release of Benjamin Fondane from Drancy, but information is very vague and less credible. Three others tried and failed to secure his release, the Romanians Emil Cioran and Stephane Lupasco (physicist & philosopher), and French writer Jean Paulhan.

Ionesco in his journals is very pro-Hebrew, pro-Israel and very anti-communist. However, in the 30's his Jewish heritage felt like a burden. M. Sebastian says in his journal that Eugene had a priest baptize his Jewish mother on her death bed in a special ceremony. (Corroborated by the Siguranta-documents archive reprinted recently by Stelian Tanase.)

Interestingly, Ionesco finally recognized his Jewish origins, after the Six Days War and declared it publicly at visit to Israel in 1967.

Ionesco was a member of the C.I.E.L. (Comité international des écrivains pour la liberté), an organization that worked for the observance of human rights in all countries and for freedom of speech for scientists, writers and artists. Eugen Barbu accused me in his newspaper of being a member of this organization, and of co-signing together with Eugene Ionesco a petition for human rights and freedom of expression. (I wish I did, because I agree with the cause, but unfortunately I did not!)

I met Ionesco several times in Paris in 1973 and 1978 and in New York in the 1980s and we discussed such things as the freedom of Romanian writers and the situation of dissidents in and out of the Diaspora as well as the publication of his books (Jocul de-a Macelul, 1973) without his knowledge or permission and the publishing of his private letters also without permission from either party (Simona Cioculescu published private letters to Petru Comarnescu before 1989, and his private letters to Tudor Vianu were published later by one of his friends).

Zigu Ornea quotes from a 1945 letter from Ionesco to Comarnescu in which he calls Eliade a "hyena." Ornea uses this text as the supreme proof about the criminality of Eliade; after all, Ionesco knew him personally and very well. (Only a few months after this letter from 1945, Eliade and his wife were dinner guests of the Ionescos in their apartment!)

Following are the words of Eugene Ionesco at the death of the great Romanian Mircea Eliade:

"I prostrate in front of the memory of Mircea, my unforgettable friend. I am, in my moments of sadness, obliged to those who have permitted me to say that we have loved him, admired him, respected him and that once more he, Mircea does never cease to be missed spiritually and emotionally, by all of us. But his work, so rich, so immense, still exists". Signed Eugene Ionesco, member of the French Academy

Lament for Eugene Ionesco

Valery Oisteanu

Eugene, Eugene, I want to say farewell

To the father of cosmic rebellion

Hot rain wets my hair as I think again of the times

We met by chance in '78

And later each time you were in New York

I remember you dressed as Tennyson in a Virginia Woolf play

And later undressing in the NYU theater

For whom the tea brews?

How come you buy rhinoceros steaks?

There is a gaping hole in the roof of the theater

Maybe I never told you that I was accused in Romania

Of conspiring with you against the Commies

Eugene, Eugene, I keep your autographed book next to my bed

We are connected in a spiritual order of Zen-Dada

We are connected like Old Masters of absurdity

Like explosive charges before detonation

We are arrows of struggle against fossilization of our senses and emotions

Conspirators against hate

Against atrophy of inspirational trance

Of induced creative psychosis

Orgasms for the masses!

Eugene, Eugene, you are my saint of the Surreal Game

The bold strippers are lap-dancing for you

We are laughing in cascades while the last tyrannies are crumbling

And your name becomes an adjective

Like Ubuesque, like Kafkaesque, like Ionesque

Eugene, Eugene, we pray for you again and again

Eugene, Eugene.

(From the book Temporary Immortality, Pass Press, NYC, 1995)

Valery Oisteanu is a writer and artist with an international background. Born in Russia in 1943 and educated in Romania, he adopted Dada and Surrealism as philosophies of art and life. Immigrating to New York City in 1972, he has been writing in English for the past 33 years. Oisteanu is the author of 10 books of poetry, a book of short fiction and a book of essays: "The AVANT-GODS."

For the past 10 years he has worked as a columnist at New York Arts Magazine and as an art critic for Brooklyn Rail and www.artnet.com. He is also a contributing editor at www.artscap.com and a contributing writer for French, Spanish and Romanian art and literary magazines including La Page Blanche, Art.es, Balkon, Dilema, Romania Literara.

As a performer Valery Oisteanu is well known to downtown New York City audiences, performing every season with the exception of the summer, when he goes on tour abroad. He is always well-received in theaters and clubs specializing in poetry and music where he presents original Zen Dada multi-media shows in his unmistakable style of "Jazzoetry."