Apr '03 [Home]

Short Prose

Apr '03 [Home] Short Prose The Pianist |

| . | . | . | . |

Gegen Österreich.

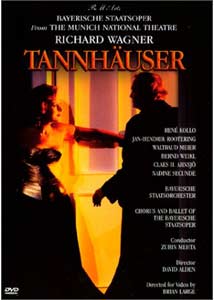

Gegen Frankreich. Gegen Frankreich, Groß Britannien, Japan, Rußland, Italien. Gegen.… It is hard to summarise a place which has been against so much. This is a litany of opposition, but what does it really mean, 'to oppose'? Had it been written, 'softly curled up against' or 'was quite indifferent to, in fact we often had sherry together and ate crackers'. But gegen? Another thing, the word is quite unrecognisable because gegen isn't an English word. I was in a Bavarian town. I was standing beneath a statue. It commemorated a regiment of light cavalry. They had been in fights against everyone, and they had won. Until.… Well, until they lost, and at that point the gegen begins to seem a bit less than a litany and somehow a confession of impotence, an anger against all this opposition, or really pathetic, impotent, a confession of defeat, a confession like no other with no possible Hail Mary as putative get out clause. I was left with a question: why? Later that day I sat and listened to the opera Tannhäuser. This is another German epiphenomenon. An opera, but not an opera in the way that operas are properly written, essentially being light entertainment. This was a serious opera, a misnomer really. Opera is light entertainment, art is entertainment. Essentially, art is a sideshow. Music is pleasant noise, rather as a car backfiring, a bomb exploding, loud farting, the groans lovers make, the slurping sound of messy eaters are unpleasant. Poetry is a whole series of pleasant words. Tax returns, bank statements, rubber stamped documents ordering the imolation of populations, electoral ballots are whole series of unpleasant words. So we know the difference, there is no confusion, yet in the case of Wagnerian opera there is a confusion. All sorts of people find his music unbearable and often refer to it as 'heavy' as opposed to 'light'. It has the serious intent to transform the world, to change the listener, to educate, to elucidate, to make an imprint on history as deep as the hoof of the horse that Napoleon rode over those snowy Alps. The analogy Wagner = Napoleon is a deeply-rooted and unshakeable myth of a man of destiny with no credible background from a remote backwater conquering the world. A man of destiny who to his followers, to his worshippers, is a world historical leader, a conqueror, to those who oppose him, a menace, a nuisance, an imposter, an 'unnatural' leader, dictator, demagogue, megalomaniac, usurper. One fought with guns and bullets, the other with notes, words. There is no confusion, military conqueror and artificer, evil and good with the same end, usurpation of the 'natural' order. On the wall in the next room is a photo of an American GI sitting on the Little Master's (for this was the name people gave him, his wife, his uncle, his goldfish, his cat…) klavier. The Little Master, his klavier, a smiling GI pockmarked with shrapnel wounds, smiling back. Which brought me back to that why question. Because these light cavalry won so much I suppose, and kept on winning. Otherwise, they would have quickly realised that warfare is a futile affair and become nature-worshipping, vegetarian pacifists. But what was the point in the first place of getting antlers locked with other peoples, the ones on the other side of the hill, who had the better water, the more sun, the plentiful supply of berries and access to the sea? Most conquerors live in desolate nowheres under barren skies where nothing ever works. They don't tend to be good at anything but the cheapest thuggery; and the fewer ideas, the more intellectually, artistically desolate they tend to be, the easier it is for them to fuck over the next village and steal the important art works amid scenes of the usual prolonged thuggery and bestial-ness. Contrasts—the art of violence, the violence of art. The art of violence is condoned, a grand spectacle so long as it happened somewhere else, not on our patch, putting paid to the usual demons and then great stiffo penises waving in the evening breeze as the delight and rapture of killing takes over from the actual momentary fear of fighting and maybe having to die. Afterwards, the writers of history tell the usual lies about the demons, the others who were destroyed, how this gives the victor the spoils, moral superiority, the ticker tape triumphal march through Valhalla.

(Paul Murphy is a frequent contributor to this magazine, and edits The Engine out of Belfast, Ireland.) [George W. Bush, a little-traveled head of state, goes to Belfast on April 7. Paul Murphy—and a dissonant chorus of many others—will likely perform for him.—Eds.] |